Irish Migrants to Merthyr Tydfil: The Burk Family

- Irish-Welsh Ancestry

- Sep 29, 2025

- 7 min read

In 1820 William Burk was born in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales. His father was a recent arrival from Ireland, driven by a desperate pursuit of work. Merthyr Tydfil, the iron capital of the world, promised work, and the Dowlais and Cyfarthfa ironworks were hungry for men. William’s own working life would have begun as a child. His world was one of near-total darkness, 12-hour shifts spent deep in the coal mines that fed the insatiable furnaces.

Work was brutal and perilous. The air was thick with coal dust, making every breath a labour. The constant threat of roof falls, explosive firedamp, and flooding was a shadow that followed every man and child who worked at those depths. Wages earned were a mixture of cash and tokens redeemable only at the company store, where prices were inflated—a system designed to keep workers in perpetual debt to their employer. He would return home to Caedraw long after dark, his skin etched with grime no wash could fully remove, his lungs rattling with the tell-tale cough that plagued every collier.

William would have lived in a damp, stone-built home, one of hundreds hastily erected to house the influx of workers. Water was supplied from a communal pump, and sanitation would have been a shared privy, a source of the typhoid and cholera that swept through the community with terrifying regularity.

As a child William Burk would have witnessed the Merthyr Rising of 1831, a desperate struggle for rights and wages where Welsh and Irish workers stood together. It is likely his father even took part. His future wife, Hannah Matthews, was living on Castle Street at the time, the location of the Castle Inn which served as a focal point of the weeklong worker’s revolt.

Living and working in Merthyr was a daily struggle for survival where families were devastated by tragedies with unthinkable regularity. This can be epitomised in a newspaper article from 1835, which recounts the story of a Mrs. Hopkins. Her first husband had been killed in a fall underground at Cyfarthfa. Then, in 1831 during the Merthyr Rising, soldiers from the 93rd Highland Regiment opened fire on an unarmed crowd outside the Castle Inn. Mrs. Hopkins' seven-year-old son was one of up to 24 killed.

The article goes on to describe a final, horrific incident. A dram from Penydarren Iron Works Pitt, on which Mrs. Hopkins was riding, collided with a steam dram from the Dowlais company. The heavily pregnant woman jumped from the dram and fell under the Dowlais steam dram. She and her unborn child were killed instantly. Just two weeks before, her husband had been badly burnt in a pit explosion.

This is one of countless incidents where tragedy was dealt to the people of Merthyr Tydfil. Families devastated by accidents were left with little support, facing an uncertain future with the workhouse as their only refuge. Industrialists amassed huge fortunes from the mineral resources of Wales, while the workers who pulled those resources from the ground—forging the iron that created the railway boom of the 1830s and 40s—survived on a pittance. Every family lived in fear of an accident or an employer's decision to cut their wages.

William Burk married Hannah Matthews in 1840 when both were twenty. They are both documented in Caedraw in 1843 when Hannah witnessed the murder of their neighbour, Mary Thomas. As she sat in her home one afternoon, she heard a scream outside. She rushed into the street to find Mary Thomas being punched and kicked. Hannah and other neighbours comforted the poor woman, who shortly died from her injuries.

On the 1851 census, William and Hannah Burk are both found living in Caedraw with their four children: William, age 10; Richard, 7; Daniel, 3; and Thomas, just 1. They shared their home with four other people, all from Co. Cork in Ireland. In the preceding years, Irish migrants had begun flooding into Wales, escaping the horror and starvation of Gorta Mór (the Great Hunger). Desperate souls were transported from Ireland as ballast in ships before being cast upon the mud banks of the Bristol Channel, where the lucky survivors crawled to shore to begin new lives. Instead of compassion, many were treated with disdain, accused of spreading disease and driving down wages. Those who shared the Burk family home in 1851 may well have been examples of these desperate people.

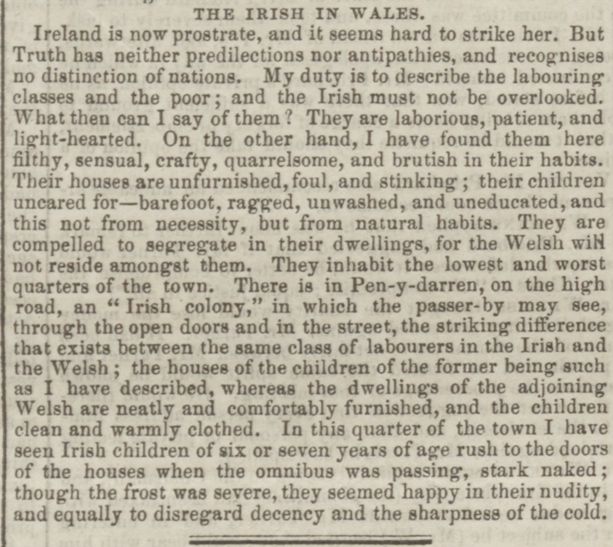

How the desperate Irish residents Merthyr Tydfil, who were facing extreme poverty, were viewed at the time can be seen in an article published in 1850 from letters commissioned by the Morning Chronicle. The writing is loaded with the racial and cultural prejudices of Victorian-era Britain. The author judges the Irish people they have encountered against the standards of middle-class Victorian values. Their failure to meet these standards is attributed not to poverty or circumstance, but to "natural habits"—an inherent, racial flaw, suggesting their poor conditions are their own fault. This racist ideology was used to justify the poor treatment of the Irish diaspora in Wales.

On 6th April 1853, the youngest of William and Hannah Burk’s children, Abigail, was born. This period saw Merthyr Tydfil hit with cholera and typhoid on multiple occasions. In 1854, Caedraw was described as having one of the worst sanitary conditions in the town. Five years earlier, William Burk had been charged by inspectors for not removing an accumulation of dung from his street. Many of the Irish immigrants in Merthyr Tydfil lived in the poorest of conditions and were often the worst impacted through disease.

When Abigail was three, her mother was expecting another child. Hannah went into labour but suffered from haemorrhaging and died on 26th October 1856, at just 36 years of age. Presumably, the child also died, as there is no record of a birth. A newspaper report details how on the day before her burial her belongings were stolen.

This tragedy left the family in a horrendous predicament. William was left alone to provide for himself and his children. How they survived is unclear. By 1861, an Abigail Burke is recorded living in Aberdare and described as an orphan. If this is her, it is unclear what happened to her father, as no death record has been found.

Abigail’s brothers, Richard and Daniel, both moved to Ferndale in the Rhondda valley to work at Ferndale Colliery, one of the largest mines in South Wales. Long before dawn on 18th November 1867, the two brothers began their shift. At 1:20 pm, a loud explosion reverberated across the valley as smoke, stones, and ash travelled up and out of the pit. A crowd of 3,000 soon gathered, desperate for news. Bodies were brought to the surface a dozen at a time. In total, 178 men and boys lost their lives, suffocated in the blast. Among them were Richard and Daniel Burke, aged just 24 and 22. The disaster left the community with 70 widows and 140 fatherless children.

The following was published in 1868 after a newspaper correspondent visited the graveyard where many of the victims were buried. He reported on the memorials that he witnessed.

Despite the early tragedies in her life, Abigail Burk married George Wickens, an ‘iron baller,’ in 1872. The young couple lived at 13 Picton Street in Merthyr Tydfil and had their first child in 1874. They named him William, presumably after her father. As was common for the times, they faced further tragedy when little William died at just two months old from convulsions.

Two years later, Abigail had a third child, naming him Daniel after one of her lost brothers. Four months after his first birthday, Daniel scalded himself while taking tea from the family table. The burns were so severe he died the following day.

Abigail and George would go on to have at least eleven children. Many did not live past childhood:

Abigail Wickens, born 1890, died age 2 of Tabes mesenterica (a form of tuberculosis).

George Wickens, born 1891, died at just one month from diarrhoea and convulsions.

Henry Wickens, born 1892, died five months later from tuberculosis and convulsions.

Charity Wickens, born 1894, died when she was just a couple of months old.

For those children who survived childhood, the danger was not over. In 1918, Abigail lost two more. Her daughter Catherine died at 23 from Phthisis (tuberculosis) and heart failure. While the family grieved at home, her eldest son, Thomas Wickens, was fighting in France during the Great War. Severely wounded, Thomas was transported to England for treatment but died on 16th November 1918. He left a widow and a four-year-old child and is commemorated with a Commonwealth War Grave at Pant Cemetery in Merthyr Tydfil.

Abigail is recorded on the 1921 census living at 77 Ivor Street in Dowlais, Merthyr Tydfil. She is listed as 70, though she was actually 69. Her husband, George, was still working at the ironworks. Even in their advanced years, they were devoted to their family, with five of their grandchildren living with them. Shortly after this census was taken, Abigail died.

The Burk family history is a stark testament to the resilience in the face of almost unimaginable hardship that people faced. Through their story, we gain a profound understanding of the price paid by countless families during the industrial age, a legacy etched not only in stone and steel but in the very memory of Wales.

Inspired by this family history? Your own story is waiting to be told.

The dedicated researchers at Irish Welsh Ancestry specialise in uncovering the lives of our ancestors. Navigating historical records and newspaper articles to piece together the narrative of your family’s past against the historical context.

Contact Irish Welsh Ancestry to research your own unique family story.

Irish Welsh Ancestry have published two books on family histories.

Comments